|

Biological Alchemy as Salvation of the Soul

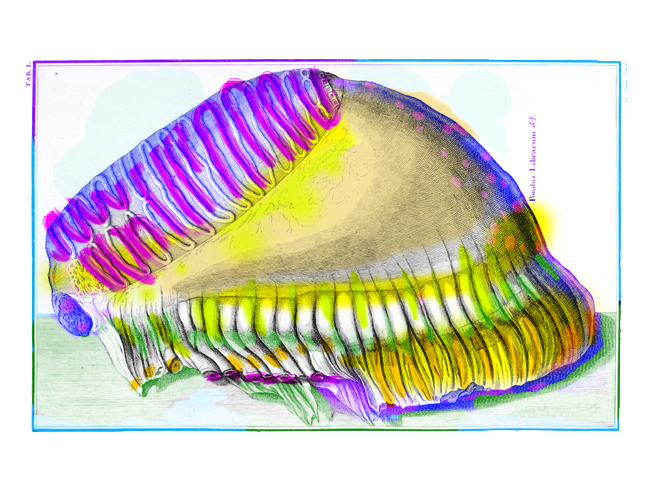

by Yuko Hasegawa, 2006 Gerda Steiner and Jörg Lenzlinger began collaborating in 1997. Their work engages matter in a process of reproduction and creation; they explore the reactions between different kinds of matter within a given space and, by establishing relationships between physical, organic, and immaterial elements, produce mutation. In their transformation into organic entities, even trash and plastic waste become mystical. The process of transmutation, including crystallization, can be described as a chemical or biological reaction in which fusion results from an encounter between materials. lt is not only alchemy of matter but also alchemy of meaning. Steiner and Lenzlinger generate multiple narratives with their mutated matter. When entered into a spatial frame, these narratives combine to form one overall, nonsequential story. The way the work is constructed follows certain patterns. The artists are conscious of the narrative capacity of a site and reconcile different worldviews within it. In "Falling Garden" (2003) in the San Staë church in Venice, the artists created a suspended garden for the deer that is said to have appeared in a miracle that made San Eustachio eligible for sainthood. The visitors lie on a bed placed over the grave of the doge buried in the church and looked up at the garden, as if assuming the doge's line of vision. The multicolored array of items suspended from the ceiling, dancing wiIdly in midair, would have been a feast for the magistrate's eyes. The objects had been gathered by Steiner and Lenzlinger during travels around the world - plastic berries from India, baobab seeds from Australia, a cat's tailt from China and artificial flowers. On the floor, vividly colored urea crystals grew on the floor. The artists' "Brainforest" (2004), created at the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art in Kanazawa, Japan, incorporates some of the cells/elements of "Falling Garden", but represents a further development. The interior of the human brain - with its complex connections and elaborate entanglement of neurons - is juxtaposed with a rainforest. Located in one of the galleries scattered like islands throughout the circular art museum, "Brainforest" was based on the organizing concept of the exhibition itself: the various installations complemented one another with polyphonic resonance. Steiner and Lenzlinger associated this notion with the workings of the mind. Paper flowers and birds made of flower petals by the residents of Kanazawa, tree branches gilded by craftsmen, and colorful cables from electrical appliances and computers hung from the ceiling and connected like synapses. When visitors looked up, it was as though they were looking at their own brains turned inside out. With Steiner and Lenzlinger's intervention, objects created by many were crystallized, with urea as the medium, or combined to form hybrids, resulting in an astonishing biodiversity that served as a metaphor for the vast range of thoughts that are activated by synapses. The visually and coloristically rich work on the one hand suggests a festive fantasy, and on the other refers to socio-critical, historical, and cutting-edge biological theories. The artists' encouragement of public participation in "Brainforest" is further enhanced in "The Found & Lost Grotto of Saint Antonio" installed at Artpace. Unclaimed items from "The Found & Lost Grotto of Saint Antonio" as well as objects that the artists found in the streets of the city are suspended inside a cave - a tent made of white fabric. Many of the elements were inspired by the role and attributes of Saint Anthony-the paintings of lilies at the entrance, the texts, and the bible placed toward the rear as if in a sanctum, from which crystals overflow. A multitude of objects - including a medal fused to a cockroach, a ten-dollar bill, a credit card, and a recorder - float at eye-level inside the cave. A can opener, a slingshot, and a vegetable peeler form a minimal installation, while a doll in a bathing suit, with an orange plastic object shaped like a seashell protruding from its back, springs from a rock. Together with a suspended blue toy seahorse, the doll creates a poetic ocean fantasy in one corner of the space. It is a premise of the piece that if visitors see an item that reminds them of a lost memory, they are welcorne to take it. In exchange, they must draw the object and describe the lost memory on a card and leave the card in place of the object. Not long after the exhibition opened, the brightly colored floating objects appeared to have been transformed into fascinating drawings. This work examines, indeed makes a science of, the meaning of loss. In the consumer society of the American West, Steiner and Lenzlinger present a thought-frame that considers the cycle of acquisition, loss, and recovery. The return of items that have been discarded and forgotten prompts a reevaluation on the part of the viewer. This productive cycle is reinforced by the analogy to biodiversity that Steiner and Lenzlinger propose through the use of plants, fertilizer crystals, and other organic matter. Steiner and Lenzlinger enable us to view our world from both microcosmic and macrocosmic perspectives. On a microcosmic level, our imaginations are stimulated and create a new sense of value. This is not value in the sense of the worth of items for consumption, but value as a quality that inspires creativity, something comparable to a fertilized egg or a cocoon in its potential for generation. On a macrocosmic level, Steiner and Lenzlinger vividly evoke memories and transform them into a contemporary narrative. What we are presented with is an image of the future that is biologically diverse and energetic (and includes viruses and pollution). Steiner and Lenzlinger use these perspectives to make the place we inhabit richer and more fertile. |